Black History Month: 100 Years Before Rosa Parks, Elizabeth Jennings Made History

by Kathy Grear 02/09/2018As an African-American woman living in New York City before the Civil War, Elizabeth Jennings was at the mercy of the whims of white people.

Sometimes, she was able to take the first streetcar that came her way and she could get on with her ordinary life as a schoolteacher and church organist. Other days, she was denied passage and told to wait until another streetcar came along, one with a sign that said “Colored.”

On July 16, 1854, Jennings encountered a particularly ornery white streetcar conductor, who refused to let her board. Jennings got on anyway.

“I did not wish to be detained,” she wrote, in an account published three days later by the New-York Daily Tribune.

Simon Douglas was one of the last surviving Civil War veterans. He lived in Fairview, where residents are memorializing him for Black History month at the Fairview Library. Patt Mazzeo, the Borough Historian for Fairview and Silvio Laccetti, a Fairview resident who is donating books to the library, including Douglas’ story, look at a painting of Douglas’ home.

The conductor dragged Jennings off the streetcar. She got back on. A police officer was hailed, and Jennings was tossed off the streetcar once more. She was left there on the street, dazed and bruised, while the streetcar drove on.

It was just an ordinary day for the racist bullies who prevented Jennings from getting to church on time. But Jennings had had enough. And she had witnesses, black and white, willing to stand by her. She had the power of the press behind her, the support of the black community, and legal representation by a future president, a young lawyer named Chester A. Arthur. Elizabeth Jennings would get her day in court.

One hundred years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, Elizabeth Jennings fought for the basic right to ride a New York City streetcar in peace. And she won.

The author and journalist Amy Hill Hearth has kept the story of Elizabeth Jennings close to her heart for more than 20 years. She first became aware of Jennings while living in Ossining, New York, near the abandoned summer home of Chester A. Arthur. Curious about the president, she began to do research, and learned that in his youth he had been a lawyer who had taken on cases for equal rights for African Americans. One of them, she learned, was Elizabeth Jennings v. Third Avenue Railroad Company.

Like a detective, Hearth began to snoop through library stacks and microfilm machines, in search of clues about Elizabeth Jennings. As a reporter, Hearth knew a good story when she heard one.

“I really enjoyed doing this as a hobby,” she said, noting that she once spent Valentine’s Day with her husband researching Jennings at the New York Public Library. “I enjoyed it as an unfolding mystery.”

Ruth Ann Butler talks about her involvement in some of the first lunch counter sit-ins in Greenville during the civil rights movement. Lauren Petracca/Staff

But she kept the mystery to herself, mainly because she had work to do on other articles and books, including the one that would make her a best-selling author.

“Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years” grew from a New York Times article Hearth wrote about Sadie and Bessie Delany, two accomplished centenarians who were the daughters of a man born into slavery in the South. Hearth’s 1993 book was later adapted for Broadway, by Emily Mann, artistic director at McCarter Theatre in Princeton, and as a TV movie for CBS.

The sisters’ wit and common sense, along with their eyewitness accounts of the Jim Crow era, inspired Hearth and encouraged her natural curiosity about the stories of little-known historic figures. The Delany sisters also urged Hearth to write more books, and she thinks they would be pleased to see Jennings’ story given its due.

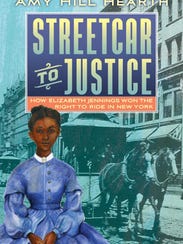

The memory of her time with the Delany sisters, along with a nudge by another friend who told Hearth she had a responsibility to tell the story of Jennings’ life, convinced the author to wrap up her research and start her 10th book. “Streetcar To Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won The Right To Ride In New York,” was published in January as a book for middle-school readers by Greenwillow/HarperCollins.

“You get attached to your subjects,” Hearth said, “and I was frustrated that her story hadn’t been told. She deserved a book.”

“Streetcar” tells the story of how Jennings, who later moved to Eatontown, undermined New York’s de facto segregation, and how she went on to found the city’s first free kindergarten for African-American children. It also examines how Jennings’ success was helped by the support of the middle-class black community and its leaders, including her father, Thomas L. Jennings, and Frederick Douglass, who championed her cause in his eponymous newspaper.

“I want them to know that the Internet gets a lot of things wrong,” Hearth said. “As little as there is about Elizabeth Jennings on the Internet, a lot of it is wrong. They get her age wrong. There’s a picture on the Internet that is said to be of her father, but it’s not him. You can’t just copy-and-paste and assume it’s going to be accurate.”

Things To Do: 12 museums to visit in winter

Because there was a law on the books supporting equal rights on streetcars, Jennings’ case should’ve been a slam dunk. Yet everything hinged on whether Jennings was deemed a credible witness. Simply by taking her case, Arthur boosted her credibility, and jeopardized his own.

“The vast majority of lawyers in that time would not be interested in taking the case of a black woman who was mistreated on a streetcar,” Hearth said. “It was unpopular and brave of Chester Arthur to do this. He should be getting credit now, because he was ahead of his time and very progressive.”

Hearth, who lives in Little Silver with her husband, Blair, can trace her paternal family’s history back to pre-Revolutionary times, when her ancestors lived in Toms River. She values roots, reputations and legacies. She spent her early childhood, in the 1960s, in Columbia, South Carolina, where she noticed water fountains marked “White” and “Colored.”

Video View by Dennis Richmond Jr. of Yonkers about the importance of Black History Month. Wochit

“We had completely segregated schools, even though that was against the law,” Hearth said. “Every day, black kids would get on a bus and go in one direction, and white kids would get on another bus and go in the other direction. We had a brand-new bus; theirs was falling apart. At the end of the year, I knew that our beat-up books went to the ‘colored’ school.”

In fourth grade, she had to write a report on a woman she admired from history. Her teacher handed her report back to her, ungraded, and told her, “You have to pick a different topic.”

Hearth had chosen to write about Harriet Tubman next.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.Only registered users can comment.