A Winning Strategy: Protest & Political Action – Message, Means and Methods

by Norman Hill 07/01/2020

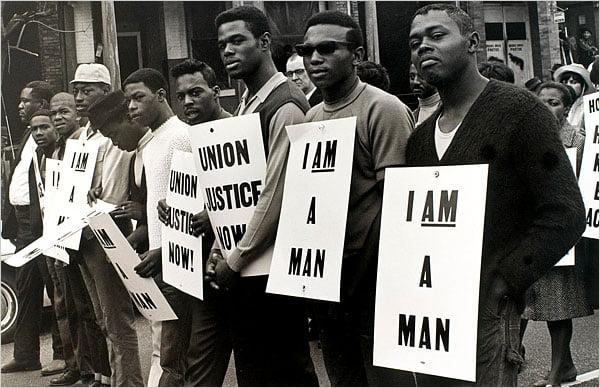

Builder Levy’s photo of marchers in Memphis in 1968. High Museum of Art

In the wake of global protests following the recent police murder of George Floyd, I am moved by the stunning use of direct action. I am especially gratified to see so many Americans of many shapes, shades, ages and orientations flexing their First Amendment rights to condemn the killing of yet another unarmed, black man while demanding meaningful reforms.

Yet, I am troubled.

I am a longtime veteran of the civil rights and labor movements. In fact, I met my wife, Velma, in 1960 on a picket line. Together, we began as young, committed activists and, eventually, became leaders in our own right. Early in our relationship, we led a demonstration to desegregate a public beach in Chicago that ended in white, vigilante violence. As a result, Velma sustained a head injury that, during the following year, led to a miscarriage that cost us our son.

Along the way, we were guided by mentors like A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. Congressman John Lewis is a friend. By the mid-1960s, we joined Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rustin at the home of former U.S. ambassador and Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, then one of King’s closest confidants, to plan and discuss civil rights strategies and tactics.

Earlier that decade, Velma and I were part of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; I worked closely with Rustin, who Randolph had placed in charge of what, almost 60 years later, stands as an iconic, high water mark of the protest era.

And while no demonstration of the civil rights era has ever drawn the vast numbers of protesters that the current manifestations of movement methods have, I, nevertheless, fear that an essential element is missing: Central leadership.

That troubles me.

Of course, I have been dismayed by the violence and vandalism that had bedeviled some of these demonstrations early on. King was similarly disappointed in the last days of his life in 1968 when a youth gang joined his march in Memphis, Tenn. in support of that city’s striking sanitation workers. The gang used the demonstration as a cover to loot and destroy property. I was there.

If King, and other civil rights leaders of his day, taught us anything, it was that effective protest is peaceful and nonviolent. They, however, also taught us the enormous advantages of a fully engaged central leadership.

A hallmark of the civil rights movement was its meticulous planning. Even the placards displayed by participants during the March on Washington, for instance, were overseen and approved by the march’s central leadership. And it should not be overlooked that the march, and its demands, led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Major decisions like whether King should carry his message of racial equality and economic justice to the North were hotly debated and considered, before he ventured to Chicago in 1966 to lead the Chicago Freedom Movement.

There was no message drift, or ambiguity.

While I applaud the logistical mastery of today’s protests – its leaders expertly marshalling, for instance, the wheels of social media – I am disturbed by frequent fracturing of the message, means and methods of what the protesters are attempting to accomplish.

For example, it is hardly unusual to see in a single gathering of demonstrators a clash of conflicting ideas — groups calling for reform, others for revolution, and others still for anarchy.

The civil rights movement was anchored in coalition politics, not simply collections of political factions. It is a serious mistake to put forth slogans that split coalitions. The chief preventative is strong, central leadership.

I realize that Black Lives Matter, founded online in 2013, has animated much of the foundational work of these protests. It also prides itself on not exerting strong, central leadership, but instead, favors deferring to community-based leadership, what its founders have called “participatory democracy.”

While this is laudable in some ways, the costs of not having clear organizational structure and hierarchical leadership comes at a high price.

The rising confusion over the call to “defund” police departments across the country is one such example. This demand has been a highly visible product of the demonstrations, held high on signs and articulated by a range of protesters, some identifying themselves as leaders.

Unfortunately, the term is open to a range of interpretations, from shifting some funds away from classic police departments in favor of greater spending on social problems and agencies to address them, to the wholesale shutting down of police departments.

President Trump has quickly crawled into the confusion, making it an anti-protest talking point.

Additionally, Trump had focused on a group of protesters who had taken over a police precinct building in Seattle’s Capitol Hill district, also known as CHOP. In the weeks it has been tensely held, city officials ceded the area, a decision Trump described as a sign of the city’s failure to act boldly. However, on Wednesday, city police and sanitation workers literally swept the area, removing protesters and arresting those who resisted – without major incident.

Yet, I am left wondering if this seizure of CHOP was a deliberate tactic of protesters, or simply a consequence of splintered leadership. I’m convinced that neither consequence is the surest road to sustained, substantive progress while a Congressional debate over national legislation regarding police behavior goes forward.

I am left wondering if this is a deliberate tactic of protesters, or simply a consequence of splintered leadership. I’m convinced that neither consequence is the surest road to sustained, substantive progress while a Congressional debate over national legislation regarding police behavior goes forward.

In the meantime, the movement could greatly benefit from a leadership with developed strategies for protests and political action, complete with short-term goals and long range objectives.

We need, as Bayard Rustin urged the civil rights establishment more than 50 years ago, to boldly move from protest to politics.

We need to redouble immediate demands for police reform and reorganization.

As November’s national elections approach, we also must disinfect the White House of Trumpism, maintain the House of Representatives, and transform the Senate to a majority that is responsive to this reemerging movement.