‘Tis The Season To Shed Light On Kwanzaa

by Emeka Ogbatue, Asst. Opinion Editor F23., The Daily Titan 12/11/2023

When I was in middle school watching “The Proud Family” on Disney Channel, I saw an episode on the channel’s evening lineup that piqued my interest.

The episode was titled “Seven Days of Kwanzaa.” Even though I was familiar with the series, I had never seen the episode before. I didn’t even know what Kwanzaa was. I hadn’t heard about it in school, from family or even on social media.

Eager for the episode, I began watching, but before I could finish, I fell asleep. I only remembered that the main character, Penny Proud, and her family were helping a homeless family of three during the Christmas season

In anticipation of The Proud Family spin-off series, “The Proud Family: Louder and Prouder” I binge-watched the original series numerous times, including the episode I never finished in middle school.

Multiple watches of “Seven Days of Kwanzaa” taught me several things about the holiday. Among them was that Kwanzaa’s origins are misunderstood and the lack of knowledge regarding them poses a problem.

In the aftermath of the deadly Watts riots of August 1965, Dr. Maulana Karenga, a renowned civil rights activist and the current chair of the Africana Studies Department at Cal State Long Beach, created Kwanzaa in 1966 as a way of rooting African cultural values among Black people in America.

Derived from the Swahili term “matunda ya kwanza” meaning “first fruits,” Kwanzaa is celebrated annually from Dec. 26 through Jan. 1. During this seven-day period, one cultural principle is practiced each day in one’s personal life and community. The purpose of the celebration is to better understand and connect to African heritage.

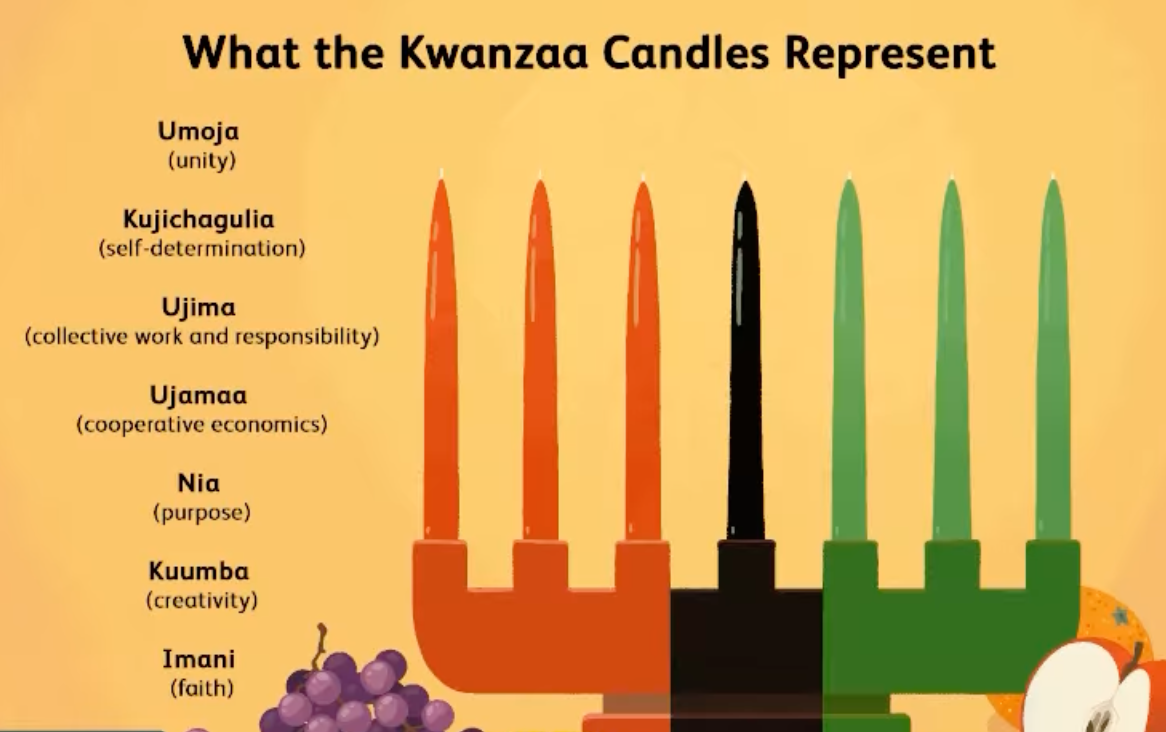

These seven principles are known as the “Nguzo Saba” and are represented in physical form with Pan-African-colored candles.

The first, Umoja, or unity, is practiced on Dec. 26 by lighting a black candle. Kujichagulia, or self-determination, is practiced on Dec. 27 with the lighting of a red candle. Ujima, or collective work and responsibility, is practiced on Dec. 28 with the lighting of a green candle. Ujamaa, or cooperative economics, is practiced on Dec. 29 with the lighting of a red candle. Nia, or purpose, is practiced on Dec. 30 with the lighting of a green candle. Kuumba, or creativity, is practiced on Dec. 31 with the lighting of a red candle. Finally, Imani, or faith, is celebrated on Jan. 1, starting the year off with the lighting of a green candle.

Ways of practicing Kwanzaa’s principles, such as Ujima and Ujaama, can be done by engaging in volunteer work and supporting Black-owned businesses. In contrast, others, such as Umoja and Kuumba, can be done by trying new activities like creating art, music and writing.

Despite these honorable intentions, Kwanzaa is only celebrated by a high of 12 million people in the United States, and even fewer people celebrate it internationally.

Kwanzaa doesn’t receive as much recognition as other Black cultural holidays, such as Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Juneteenth, but it doesn’t have to do with its celebration elements. Instead, it is the lack of recognition the holiday has received in the mainstream media and social and political institutions.

Gwendolyn Alexis is a professor of African-American studies at Cal State Fullerton.

She said that she had heard passing mentions of Kwanzaa during her childhood and early adult years, but didn’t understand what it was despite being in activist circles as early as age 8.

“This will be, at 67 years old, the first time I will celebrate Kwanzaa. All of our culture was taken. All of our traditions were taken from us,” Alexis said.

Alexis also emphasized what Kwanzaa means to her as an activist and an individual. “The seven principles, they’re so important to me. It’s about community, it’s about having our own, creating our own,” Alexis said.

Alexis’ experience relates to my own and to others I have met. The experience of having a passing mention of Kwanzaa but not understanding what it is until much later due to limited exposure is common within the community.

Alexis suggested that CSUF should highlight Kwanzaa and other Black holidays more noticeably on their social media pages. The university could also fly the Pan-African flag — a flag that represents Black liberation — during Kwanzaa and other Black holidays to demonstrate solidarity with Black students and faculty during the celebration.

Kwanzaa is meant to be a cultural celebration. It is not racially exclusive or religious, nor does it replace other winter holidays such as Christmas, Hanukkah or Diwali. My exposure to Kwanzaa through “The Proud Family” was one of the few instances where the holiday was highlighted in mainstream media, and that episode was released in 2001.

It’s 2023, and when I search about it, I see very few media references to it. I don’t see it being recognized at schools or by government institutions. Even worse, I see rumors and conspiracy theories about how the holiday is a false flag operation from the deep state that is meant to divide people during the holidays, which is far from the truth.

Actively promoting the recognition of Kwanzaa will help in promoting its importance. If not, its meaning will be distorted and erased from Black culture.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.Only registered users can comment.